The pure public good has been the subject of most economic analysis of public goods. In many ways the pure public good is an abstraction that is adopted to provide a benchmark case against which other, more realistic, cases can be assessed. A pure public good has the following two properties:

Non-excludability: if the public good is supplied, no consumer can excluded from consuming it.

Non-Rivalry: Consumption of the public good by one consumer does not reduce the quantity available for consumption by any other.

In contrast, a private good is excludable at no cost and is perfectly rivalrous: if it is consumed by one person, then none of it remains for any other. Although they were not made explicit, these properties of a private good have been implicit in how we have analyse market behaviour.

The two properties that characterise a public good have important implications. Consider a firm that supplies a pure public good. Since the good is non-excludable, if the firm supplies one consumer, then it has effectively supplied the public good to all. The firm can charge the initial purchaser but cannot charge any of the subsequent consumers. This prevents it from obtaining payment for the total consumption of the public good. The fact that there is no rivalry in consumption implies that the consumers should have no objection to multiple consumption. These features prevent the operation of the market equalising marginal valuations as it does to achieve efficiency in the allocation of private goods.

In practice, it is difficult to find any good that perfectly satisfies both the conditions of non-excludability and non-rivalry precisely. For example, the transmission of a television signal will satisfy non-rivalry but exclusion is possible at finite cost by scrambling the signal. Similar comments apply, for example, to defence spending, which will eventually be rivalrous as a country of fixed size becomes crowded and from which exclusion is possible by deportation. Most public goods eventually suffer from congestion when too many consumers try to use them simultaneously. For example, parks and roads are public goods that can become congested. The effect of congestion is to reduce the benefit the public good yields to each user. Public goods that are excludable, but at a cost, or suffer from congestion beyond some level of use are called impure. The properties of impure public goods place them between the two extremes of private goods and pure public goods.

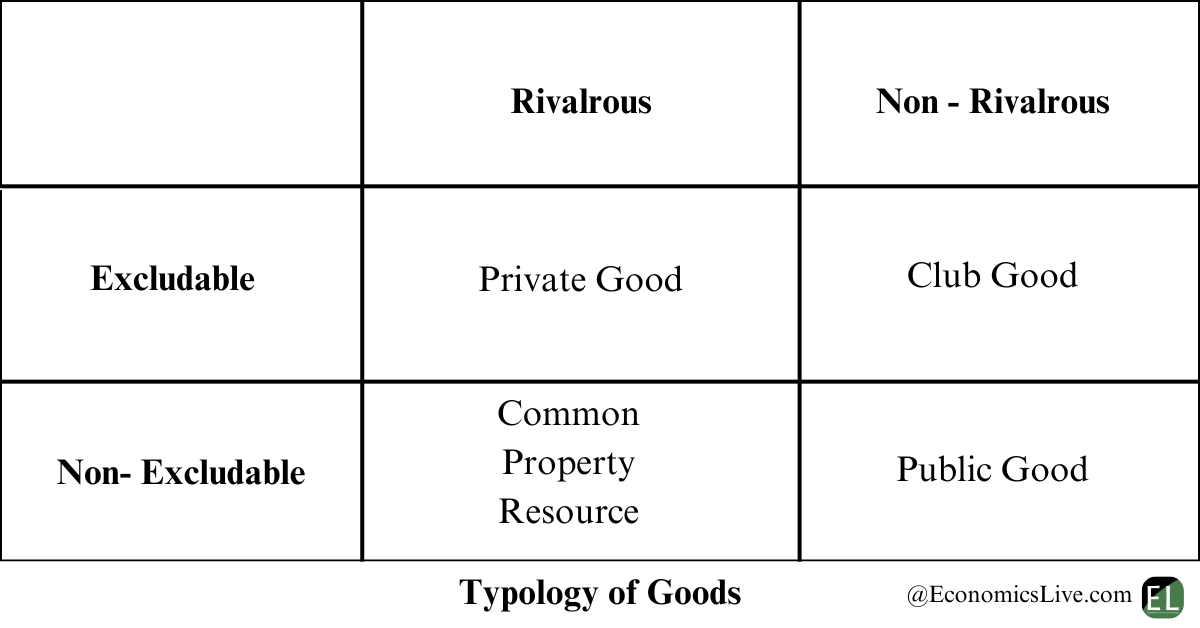

These goods vary in the properties of excludability and rivalry. In fact, it is helpful to envisage a continuum of goods that gradually vary in nature as they become more rivalrous or more easily excludable.

The pure private goods and the pure public good have already been identified. An example of a common property good is a lake that can be used for grazing by any farmer. This class of goods are usually know as the commons. The problem with the commons is the tendency of overusing them, and the usual solution is to established property rights to govern access. This is what happened in the sixteenth century in England where common land was enclosed and became property of the local landlords. The landlords then charged grazing fees, and so cut back the use. In some instances property right are hard to define and enforce, as is the case of the control over the high seas or air quality. For this reason only voluntary cooperation can solve the international problems of overfishing, acid rain, and the greenhouse effect. Club goods are public goods for which exclusion is possible. The terminology is motivated by sport clubs whose facilities are a public goods for members but from which nonmembers can be excluded.