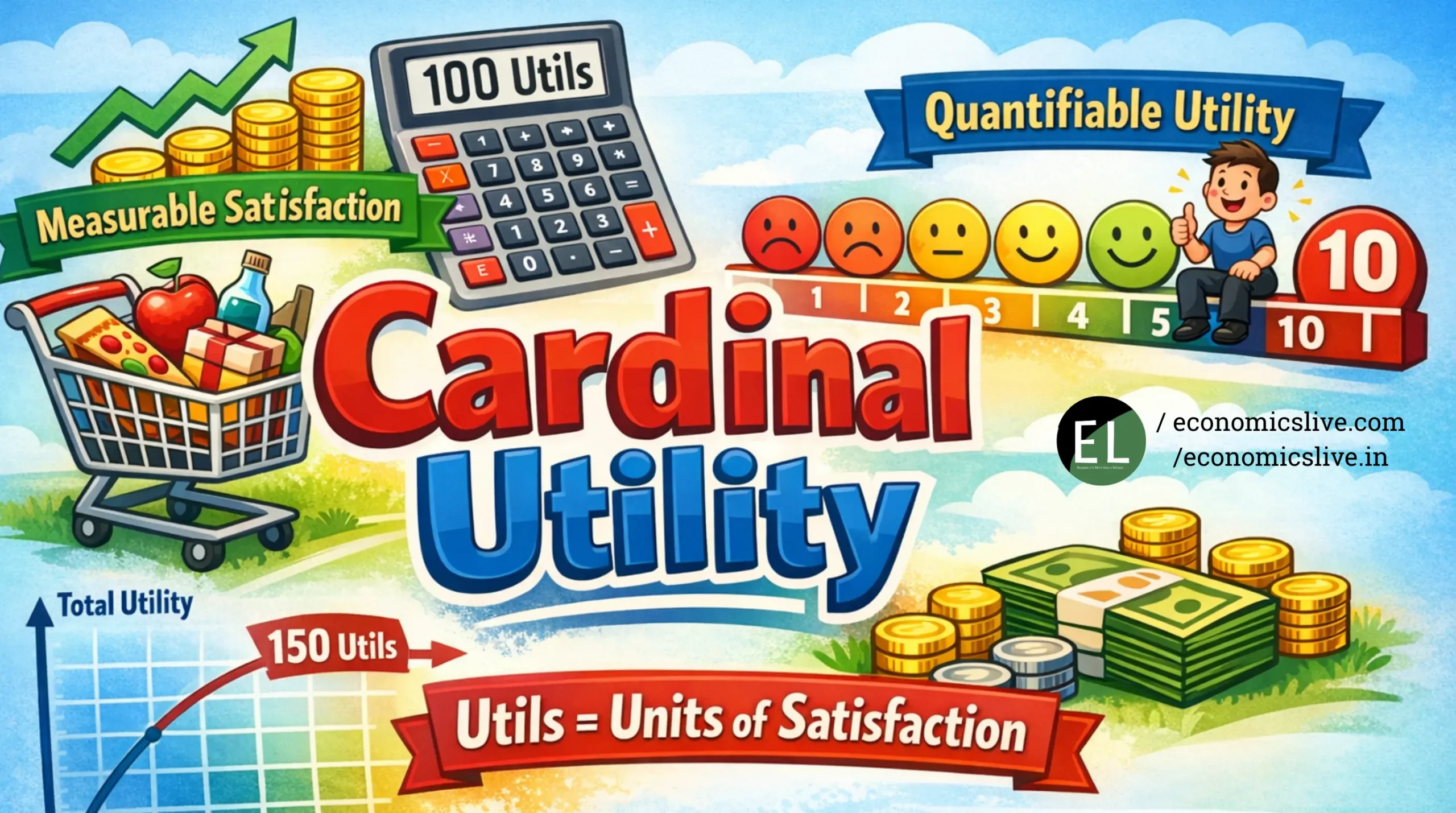

A rational consumer aims to allocate their income among available goods to yield the highest possible satisfaction or utility, given their income and prevailing market prices. This principle is known as the utility maximization axiom. The cardinalist school proposed that utility is measurable. Economists have offered various methods for measuring it. Under conditions of certainty i.e., when market situations and income levels are fully known during the planning period, some have argued that utility can be expressed in monetary terms, representing the amount of money a consumer is willing to forgo for an additional unit of a commodity. Others have suggested measuring utility in subjective units, referred to as utils.

Assumptions

1. Rationality: Consumers are assumed to be rational, aiming to maximize their utility within the limits of their given income.

2. Cardinal utility: The utility derived from each commodity is measurable, making it a cardinal concept. The most practical measure of utility is money, specifically, the amount a consumer is willing to pay for an additional unit of a commodity.

3. Constant marginal utility of money: When utility is measured in monetary terms, it is essential to assume that the marginal utility of money is constant. A standard measure must be stable; if the marginal utility of money changes with variations in income, it becomes an unreliable or “elastic” unit of measurement.

4. Diminishing marginal utility: The satisfaction or utility derived from each additional unit of a commodity decreases as the consumer acquires more commodities. This principle is known as the law of diminishing the marginal utility.

5. Total utility of a basket of goods: The total utility obtained from a combination of goods depends on the quantity of each commodity consumed. If there are n commodities with quantities , total utility is represented as

Early versions of consumer theory assumed that the total utility was additive.

However, this additivity assumption was later abandoned because it implied that the utilities of different goods are independent which is an unrealistic and unnecessary premise for cardinal utility theory.

Equilibrium of the consumer

Consumer equilibrium can be explained first with a single commodity and then extended to multiple goods. The basic idea is that the consumer arranges spending so that no further reallocation of money can increase their total satisfaction.

Single commodity case

Consider one good, , and money income , which can either be spent on or kept as unspent. The consumer is in equilibrium when the marginal utility of is equal to its market price , that is

If , the consumer can raise the total utility by buying more units of xx. If , the consumer benefits by reducing the quantity of purchased and keeping more income unspent; thus, utility is maximized when .

Multiple commodities case

With several goods, the consumer reaches equilibrium when the ratio of the marginal utility of each commodity to its price is the same for all goods:

This means that the extra utility obtained from the last unit of money spent is equal for all commodities. If one good yields a higher marginal utility per rupee than others, the consumer can increase overall welfare by spending more on that good and less on others until this common ratio is equalized.

The extra utility obtained from the last unit of money spent must be equal for all commodities. If one commodity yields a higher utility per unit of money than the others, the consumer can raise overall welfare by spending more on that commodity and less on the rest until this equilibrium condition is satisfied.

The extra utility obtained from the last unit of money spent must be equal for all commodities. If one commodity yields a higher utility per unit of money than the others, the consumer can raise overall welfare by spending more on that commodity and less on the rest until this equilibrium condition is satisfied.

Critique of the cardinal approach

The cardinal utility approach faces several fundamental criticisms.

- It rests on the doubtful premise that utility is cardinally measurable, even though satisfaction obtained from different goods cannot be objectively quantified.

- Walras’s proposal to measure utility in subjective units, or “utils,” also fails to resolve this problem in any convincing way.

- The assumption of a constant marginal utility of money is likewise unrealistic, since the marginal utility of money changes as income rises or falls, making money an unreliable measure of utility. Finally, the law of diminishing marginal utility is essentially a psychological generalization based on introspection rather than direct empirical proof and is therefore simply assumed rather than rigorously established.